Unit London

Kevin Klamminger

06.Nov.24 – 09.Jan.25

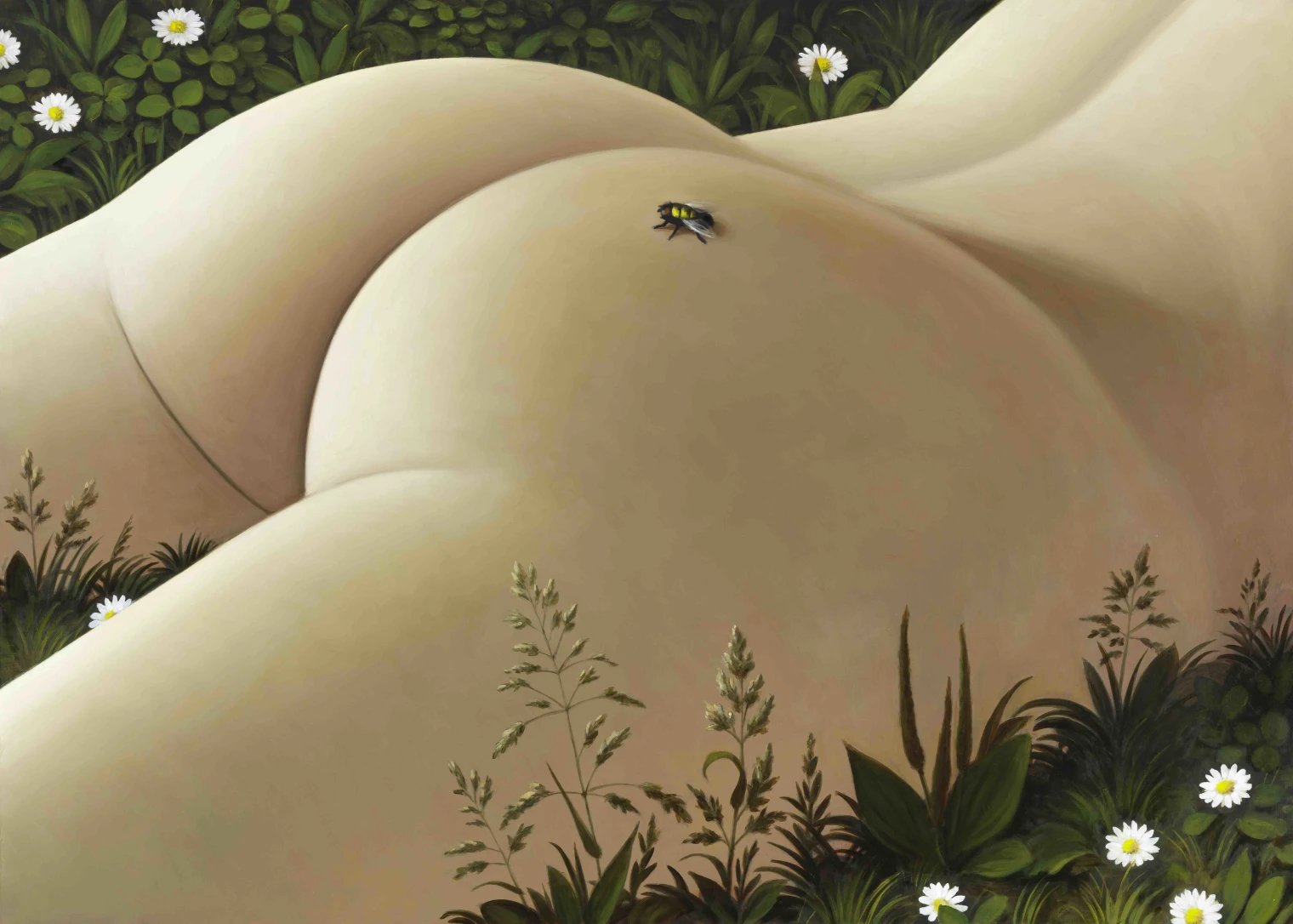

At its core, Kevin Klamminger’s first solo exhibition with Unit explores an interplay of contradictory forces. Influenced by a balance between conscious and unconscious minds, Promethean Approach presents a series of paintings that combine an almost hyperrealist visual language with a surreal atmosphere.

Paying close attention to light, the body of work is unified by its colour palette, a sunset glow of oranges, yellows and reds. The artist’s depiction of light requires a focus on its opposite as darkness and shadow bring balance to each painting. The interest in opposition evolves organically from Klamminger’s intuitive process, reflecting the internal discussion that takes place in his mind every time he works. Through this process, Klamminger strives to switch off his analytical mind, following instincts and intentions that are not always conscious.

Even though Klamminger’s intuitive process leans into chance, representational elements seep into each artwork, grounding the viewer in the real world despite dreamlike settings. These elements make up a body of symbols: horses, butterflies, shields and spears appear like clues that draw us into a search for meaning. While Klamminger does not abdicate responsibility for the significance of these symbols, he never wants to foreclose the interpretations of others. He does not ascribe any element with specific meaning, hoping to leave each painting up to the viewer’s interpretation. In turn, the viewer’s search for individual meaning becomes crucial to the artist’s process and to the artworks themselves.

Klamminger himself often wonders at the meaning behind these representational elements, which often materialise on his canvases without warning or prior thought. For example, the horse appears in various forms across the body of work. Klamminger is at once intrigued by the animal’s powerful musculature and its anxious nature. It is the idea of opposing forces that once more becomes important, as Klamminger ponders the paradoxical relationship between fear and power that is embodied in the horse’s image. These ideas are explored in the painting Veni, Vidi, Vici in which two horse riders collide on a beach. The sunny Mediterranean landscape clashes with the painting’s theme of combat. However, when we look closer, the two riders lose their clarity. The horses are strangely deformed and twisted, appearing almost as moving anatomical studies. White fabrics billow dramatically against a blue sky, but the riders themselves are disembodied, recognisable only from their helmets and shields. The initial heroism of the work gives way to a sense of fatalism as Klamminger upends our expectations of a traditional theme.

In the circle of Anger, the swampy river Styx becomes the battleground for the wrathful and sullen. Kenrick MacFarlane confronts us with the explosive emotions of wrath, expressed in a suffocating rage. In an unsettling portrayal of the chaotic and destructive nature of anger, MacFarlane’s work echoes the eternal struggle to defeat one’s inner demons. Trapped in a violent, relentless cycle, the figures desperately try to escape their own fury.

Becky Tucker’s Crypt provides a chilling exploration of the Sixth Circle of Heresy, where heretics are entombed in flaming crypts. The cold, ceramic exterior of the piece contrasts with the searing flames that are implied to burn within. The intricate patterns that adorn Crypt suggest a smothering entanglement, where the soul is forever trapped within the walls of its own making.

At this pivotal moment in Dante’s journey, we transition from the hopeless depths of Hell to the more hopeful landscape of Purgatory, as envisioned by Rex Southwick. His is an artistic reimagining of Dante’s mountain as a modern-day cliff-side villa. This luxurious structure, teetering on the edge of a cliff, serves as a striking visual metaphor for the souls striving to cleanse themselves of sin while still tethered to the luxuries of their past lives.

After emerging from Purgatory, we return to the final depths of Hell, where the consequences of unrepentant sin grow even more severe. In the Seventh Circle of Violence, Oleksii Shcherbak’s beasts evoke the savagery of the violent souls punished for their brutality. Oleksii’s artworks propel us deeper into this realm, which is divided into three rings, each punishing different forms of violence. Guarded by the Minotaur, the circle is home to centaurs that shoot arrows at those who committed violence against others, while alluring harpies torment those who were violent toward themselves.

Malene Hartmann Rasmussen’s ceramic snakes dominate the Eighth Circle, home to the fraudulent. In this realm, panderers, seducers, and thieves are tormented by serpentine creatures that embody deceit and treachery. The coiled, sinuous forms of the snakes reflect the duplicitous nature of those condemned here, slithering through the darkness.

At the very bottom of Hell, its swirling centre depicted in Yaya Yajie Liang’s Spasm, lies the Ninth Circle of Treachery. Albie Romero’s paintings draw directly from Canto XXXII, which opens with Dante’s declaration of the limitations of his poetic language in describing the haunting scenes he has observed. The inhabitants of this circle are those of the Caina region of Cocytus. They are punished by having their body frozen in Cocytus with only their heads sticking out, as depicted by Romero’s figures. Their stillness contrasts with the violence of the sins committed, capturing the ultimate punishment of those whose treachery cuts to the very heart of human condition.

Info + opening times

Unit London